With all of the credit market fireworks that leaked into stocks, the pace of economic reassurance from “authorities” has been rather steady and a bit more emphatic. Despite the attempts at managing perceptions, there has been very little actual success in persuading. In many ways this is like the unfolding ebola drama in that there is a palpable disconnect between what we are being told and what we can directly observe – not fear of the disease but wariness over the response.

That makes for an interesting comparison, given all that has transpired recently in and out of the news. You would think that many more issues would be hard pressing voter concerns only two weeks ahead of the midterm election, yet the top focus, at least in the latest AP-GfK poll, is and remains the economy. An astounding 92% of those “likely voters” surveyed (an extrapolated statistical number to be sure) say that the economy is “extremely” or “very” important to them – much greater than the second place concern, healthcare, at only 80%. The Islamic State and terrorism in general are next at less than 80%; ebola doesn’t make the top 5.

That doesn’t seem to match the constant and confident references to the unemployment rate; though it very well does if you actually consider the denominator in that fraction. The central experience of the vast majority away from asset inflation, primarily through stocks, is to be highly suspect about what they are calling an inarguable economic advance – let alone the best stretch of jobs in more than a decade.

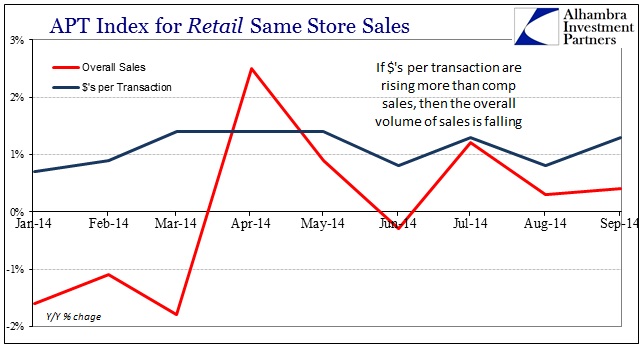

Some of that is likely due, again, to the way the economic statistics are calibrated and constructed. That realization includes how price changes affect not just psychology but actual economic standing. We have seen that in the seeming nominal steadiness in retail sales, but factoring even a minor difference in prices this year compared to last totally changes interpretation (of those looking objectively, anyway).

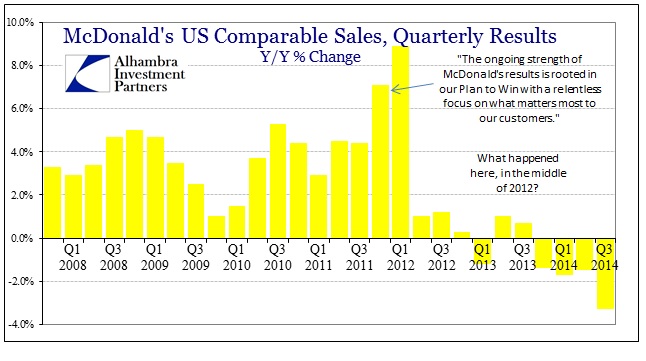

Of all the anecdotal evidence in that direction, I highlighted Target’s granular data but I also think we can add McDonalds.

The sorry state of what was a high flying establishment as recently as early 2012 provides no small indication that “something” is amiss. Adding a little more detail to McDonalds’ view of the restaurant industry, and thus as a proxy for consumer economic standing, the behavior of food prices is indicative of the same kind of attrition that is weighing on retailers, including Target and Walmart.

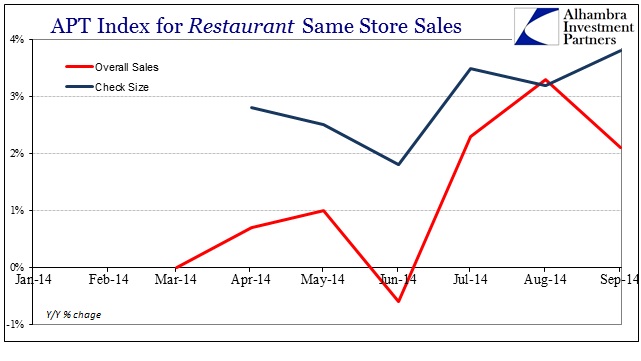

Predictive Technologies is a firm that provides “big data” services to many industries, including retailers and restaurants. While both their retailer and restaurant same store sales indices were only launched this year, they are at least created off hard data:

The APT Index includes a subset of APT’s $2 trillion in sales data. The Index aggregates data from sales registers at over 65,000 locations across the U.S. to show how year-over-year performance changes for same-store sales in the physical channel. Unlike other sources, the APT Index is based on reported sales data, allowing APT to make statistically significant observations about retail and restaurant sales.

On the restaurant side, there was a perceptible increase in same store sales in the summer, but that isn’t necessarily a hint of rising consumerism (though the suspiciously over-the-top APT commentary that accompanies their press releases echoes very much like the cheerleading that comes with the Thomson/Reuters’ SSSI and how commentary there does not fit the actual data). In fact, like Target, we get the same sense that the increase in revenue is due to prices at the expense of volume.

Outside of August, every month this year has seen overall dollar growth driven by “check size” rather than the number of transactions, or at least a combination of the two. It could very well be possible that fewer customers overall are buying more when they do show up (which would account for larger check size) but common sense and contextual intuition more than suggest it is very likely that the increase in “check size” is due far more proportionally to rising prices. Rising prices in this context would offer a comprehensive explanation for both larger “check size” and fewer transactions in tandem.

That would also offer a persuasive account for McDonalds collapsing sales. A hurting consumer might choose McDonalds but only if prices match expectations – take away the cheap price and the cheap meal no longer seems to be much of a “value.” That similar indications might be widespread across the industry, if the APT data is indeed a good proxy, is as much a macro indication as preference or taste. A robust economy can absorb price changes far more easily and with less widespread disruption than one undergoing persistent attrition.

In other words, if customers were leaving McDonalds because of something specific to only McDonalds, we would expect rising transactions throughout the whole industry, not declining. The fact that overall retailing is experiencing much the same process is very compelling toward that interpretation.

Where nominal revenue may be better than the first three Polar months of the year, overall the number of transactions has declined in every month except April. That would certainly match up with other anecdotes such as mall traffic and overall retailer traffic. Fewer people are shopping, but when they do they spend more dollars, an indication, potentially, of prices rather than economic health.

While there isn’t much of a baseline to the APT indices, they do at least provide commentary about 2013’s Black Friday results. Back in November 2013, the APT index saw 2.1% sales growth with 1.7% growth in the number of transactions (and only a 0.4% increase in the dollar amount of those transactions, by comparison). That was during the worst holiday sales season this side of the Great Recession. That pattern at least keeps consistent with other indications of prices and the erosion this year compared to last I referred to above.

This all gets back to wages, which is the signature divergence evident in modern monetarism. Like Japan, price changes (for whatever reason, as clearly the case with fast food is nonmonetary in nature given beef prices and the California drought among other factors) and wages are not durably joined. In an economic situation where that leads to revenue problems at businesses, again, a lack of actual economic progress, that is doubly distressing as those businesses already overly sensitive to costs simply become that much more entrenched in that direction – meaning less productive investment and less spending on human resources, especially less favorability toward adding payrolls while increasingly holding the line on pay.

At some point it begins to spiral backward, as people buying fewer goods and services while paying more to do so will mean less actual economy.

Stay In Touch