OK, so not all of Germany’s bellwether business sector is gaga over Christine Lagarde. The particular subset of respondents who answer the survey from that country’s ZEW, if you recall, are absolutely nuts (about “stimulus.”) Other examinations have found rather less enthusiasm; still some degree of rising optimism, but nowhere near the exuberance displayed to the ZEW.

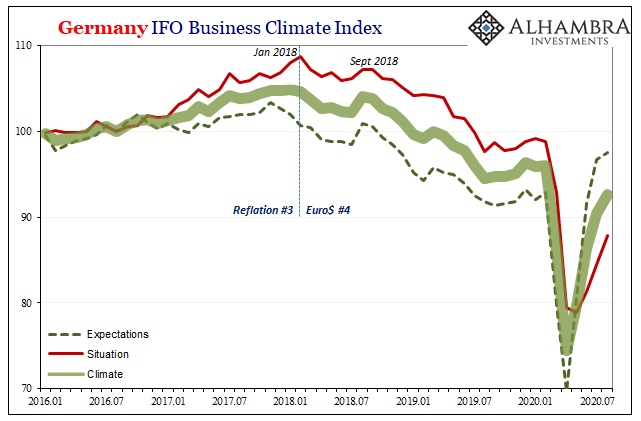

The IFO’s sentiment surveys are one such set. The overall index, which combines views on the current situation with forward-looking expectations, remains subdued in this post-GFC2 world of huge uncertainty. Like the ZEW’s other, less-heralded situation index, the same for the IFO indicates there hasn’t really been much of an actual rebound in Germany’s economy from April’s bottoming out.

Unlike the ZEW’s rocket-like sentiment index, however, the IFO’s portrays far, far less optimism that this dreadful situation is going to change anytime soon. There’s some, but the index itself in its latest reading for August 2020 is only about the same as it was heading into 2019’s slide-toward-recession doldrums.

It’s not what you’d expect to find during a forming “V.”

By comparing side-by-side the two data sets it largely confirms our interpretation of the ZEW; that particular subgroup of German business professionals is unshakably fixated on the idea, any idea, for “stimulus.” At the IFO, ECB policies especially when “augmented” by fiscal measures are warmly received, just not to nearly that same degree.

Sentiment is pulled further upward than the situation, to hugely varying degrees.

Sentiment is a tricky thing, and trickier still to legitimately measure. The German examples here suggesting that though targeting ostensibly the same thing, forward-looking expectations the ZEW and IFO are getting responses based on what have to be very different factors.

In the realm of useful analysis, do we really care about perceptions of monetary policies? That’s what central bankers are after, but it isn’t what we want to know for clues about what comes next.

Money-less modern monetary policies are an entirely expectations-based proposition; therefore the monetary policy official is very much attempting to get at manipulating the perceptions of economic (and financial) agents withing their jurisdictions. The ZEW says Christine Lagarde has performed exceedingly well at her primary task.

The reality is that her primary task is ultimately useless; which brings in the conversation about the IFO (as well as the situation estimates for both).

What about other forms of sentiment, and ways to measure it? Outside of Germany, US Economists and central bankers are absolutely glued to this idea. Though more geared toward consumers than strictly the business sector (which makes sense; the German economy is an export-powerhouse whereas the US economy, when it’s operating within tolerances, lustily gobbles up what others make), Federal Reserve policy – through the stock market – is aimed squarely at your wallet or pocketbook.

But Jay Powell isn’t the only factor playing around within US consumer expectations and sensitivities. He can’t be; the unemployment rate, specifically, has played a role as has the labor market conditions more generally. It’s more interesting where the two have diverged, such as since late 2018’s landmine.

In 2019, stocks picked themselves up from it and rode the cues from first the Fed pause and then the rate cuts followed by not-QE to higher highs. The real economy, labor market, too, was instead pulled into the globally synchronized downturn no one outside the bond market had been anticipating. Even as the unemployment rate sank lower, the brightest of these consumer sentiment measures failed to catch on to the monetary policy-fest like it and equities had.

For the last few months, we’ve noted a gap first between the huge numbers of payrolls (or employees) which had been cut during the worst parts of the March-April non-economic dislocation and the even greater cuts to total hours worked. More of the latter suggested businesses were idling (while still paying) a significant portion of their workforce, keeping some on the payrolls even though there was no work for them to perform.

The recently released productivity numbers added new corroborating details especially those for the manufacturing sector; the number of hours dropped but the level of output collapsed by even more, a lot more, tanking productivity when historically during recessionary layoff periods it should be exploding upward as businesses hurriedly, desperately seek to match lower levels of labor on their books with the lower levels of revenue still coming in the door.

More workers on payrolls than needed doing fewer hours, and what work they performed during those (recorded) hours was far less productive. A lot of on-the-books standing around? It appears so.

Why?

Before even getting to July, this divergence between hours and headline payrolls had already suggested that companies may have been holding on to more workers than the decline in output would’ve demanded. In other words, the level of output and actual work performed had declined more than the reduction in headcounts, by a lot more, leaving us to suspect businesses were holding back a sort of reserve of their own workers (who were still on the books but idle nonetheless) having them at-the-ready for when reopening got started.

The idea for businessowners would’ve been to tough it out, wait a few painful months for the “V” to show up; because we were all told how it would be as easy to turn everything back on as it had been when turning everything off. Oh, and a huge dose of monetary and fiscal “stimulus” just to make sure. Guaranteed (said the liar).

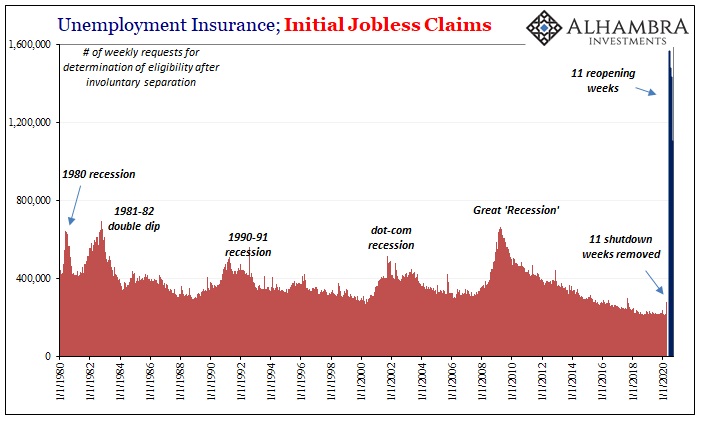

More and more, however, we’re seeing that a combination of factors appears to be restraining the reopening rebound such that it may be causing businesses in the US (and Germany) to rethink their worker “reserve.” Not only have we found this in hard data, stubborn, historically high jobless claims, this second wave seems to be showing up in US consumer sentiment, too, defying stocks, the unemployment rate, and, most of all, Jay Powell.

Second wave of economics, not COVID.

The Conference Board’s index, as you’ll note above, was down sharply in August 2020 from July. And last month’s figure was less than June’s. Not only had the index peaked two months ago, the latest reading sits lower than either April or May. Commenting on the surprisingly weak possibilities, Lynn Franco, Senior Director of Economic Indicators at The Conference Board, said:

The Present Situation Index decreased sharply, with consumers stating that both business and employment conditions had deteriorated over the past month. Consumers’ optimism about the short-term outlook, and their financial prospects, also declined and continues on a downward path. Consumer spending has rebounded in recent months but increasing concerns amongst consumers about the economic outlook and their financial well-being will likely cause spending to cool in the months ahead. [emphasis added]

The highlight portions are frighteningly consistent with this growing possibility for a second wave; businesses reaching their limits, not finding a “V”, and then letting go of their labor “reserves” because the economy was never disrupted by purely non-economic factors. GFC2 might prove to be the more lasting influence yet.

From two sets of German businesses to one group of American consumers, we know that “stimulus” is absolutely creating updrafts in sentiment. If the ZEW is the unfettered expression of raw monetary (and fiscal) policy happiness, then there’s at least some of it – if a whole lot less – in both the IFO’s as well as the Conference Board’s figures. How bad might those estimates have been without it?

Monetary policies can make certain people happy about how terrible things might be, but, once again, it’s of little use in the face of how terrible things might really be. And what’s the most terrible current prospect? The lack of a “V” materializing before too much longer which then unleashes that second wave.

We don’t know how things will shape up from here, of course, but it’s becoming clearer how on balance the “V” is, and has been, based on little more than happy thoughts residing in peoples’ heads due to little more than conditioned reflexive reactions; while at the same time a consistent picture is emerging based in data, from hard to soft, and markets, from dollar to yields (even LIBOR and basis swaps), which is already tipped and trending in the wrong direction.

Stay In Touch