The Brazil strategy isn’t, of course, truly Brazilian. Like the Spanish flu which became famous for where it was first noticed and reported rather than where it originated, this monetary policy was thought up elsewhere and Banco do Brasil is merely the central bank which decided it was worth sharing.

What is this Brazil (my term, by the way) policy? “Contingent liabilities.”

A well known advantage of issuing such contingent liabilities as currency swaps is that authorities become able to intervene in the exchange market indirectly, without affecting the money supply or varying the stock of foreign exchange reserves.

The above quote comes to us from a 2013 paper written by researchers working for Banco, sanctioned as academic proof of a very real and operational monetary program. They had published both the outlines of the philosophical framework as well as a study quantifying its stunningly awesome results.

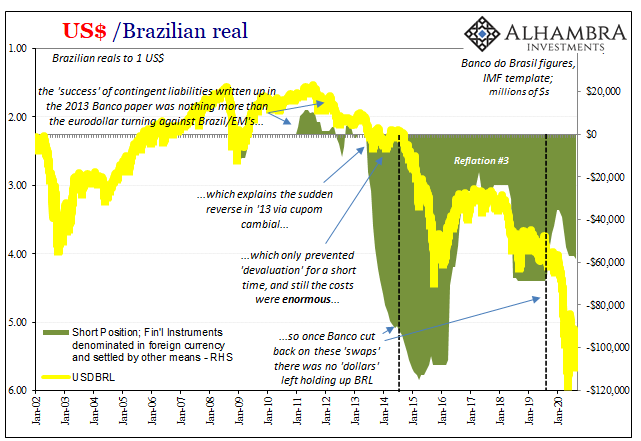

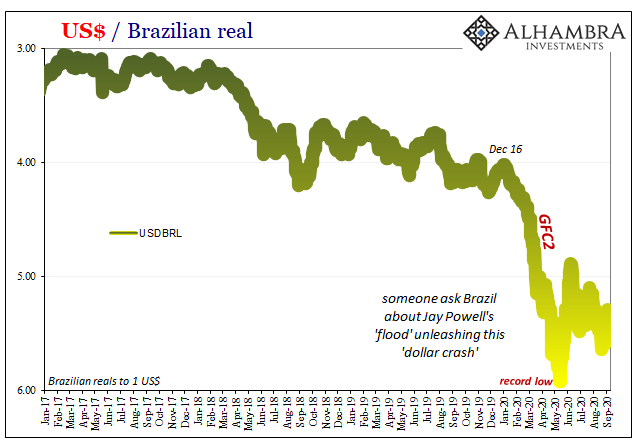

Those were taken from earlier when Banco was actively trying to weaken its own currency, the real, because of, everyone said, the Fed’s “money printing” which was destroying the dollar (everyone said) leading to what Brazil’s Finance Minister had declared in September 2010 as a “currency war.”

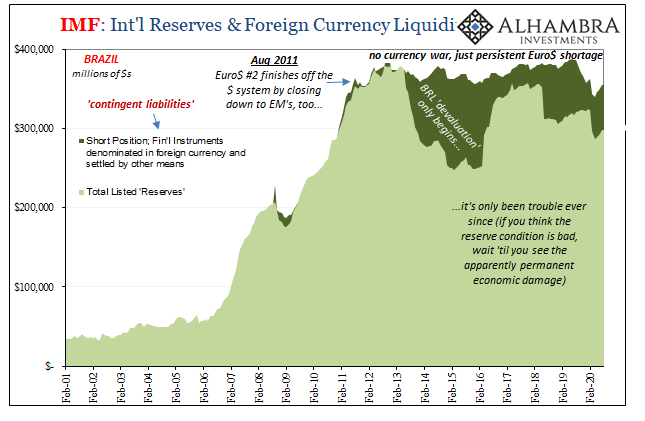

Perhaps the authors should have waited until after 2013 when “contingent liabilities” would be run up to more than $100 billion attempting to counteract the dollar’s “unexpected” strength, leaving instead Brazil exposed to what would go on to become its epic currency crash. The economy still hasn’t recovered from it, a solid dose of cold water for anyone thinking about employing this method.

For many countries, like Brazil, the fact of the matter is their own monetary systems have been dollarized; that is, internal money supply factors all begin with the central bank’s balance sheet which is loaded, often the majority, with “foreign reserves.” This makes things incredibly simple in this one respect: use those reserves in any way, subtracting them from assets, the internal money supply must also shrink in accordance.

What to do, then, when faced with a dollar problem? The whole point of having so many foreign reserves (largely US Treasuries), at least in the Economics textbooks, was as insurance for this very situation. The eurodollar market tightens making it more difficult for local banks to obtain dollars they absolutely have to obtain, shouldn’t you then be able to sell reserves and temporarily provide your banks some dollar relief?

Theory vs. practice.

In practice, doing so is a double whammy against. First, by selling reserves openly you are only inviting more trouble from the eurodollar market by advertising liquidity and other risks back to it. If banks in the global money marketplace are already becoming risk-averse, how would it help to publicize, as well as officially confirm, the nature and scale of what would have to be a major risk?

Second, the accounting. If you do end up selling reserves, the central bank’s asset side contracts which has to be met with the same on the liability (money) side of its balance sheet. The external monetary tightness is transferred internally, potentially causing, while at least amplifying, big economic problems.

The intellectual foundations of this Brazil strategy are thus quite understandable: avoid selling reserves so as to avoid the situation where you’ve painted a further external dollar target on your back while at the same tightening your own internal, domestic money supply for the trouble. If reserves are insurance, they are the most expense and least useful kind.

How does it work?

Contingent liabilities. Derivatives. Swaps and the like. Because they are “contingent”, they can be counted in various ways almost anywhere on anyone’s balance sheet. And if they do show up, it is more likely at a much-reduced, heavily-massaged valuation possibly described in some footnote buried down deep amidst other arcane minutiae.

The published, on-the-books balance of foreign reserves can, essentially, remain the same – or, could possibly be engineered to basically look any way you want. For a time.

It’s only because this strategy didn’t work during the dollar tightening period (beginning at almost the same date as the paper was published) that Brazil’s off-balance sheet footnotes grew to be so large you couldn’t help but notice (though hardly anyone seems to have noticed, even today); doing no one any favors (my contingent pun for how it worked out).

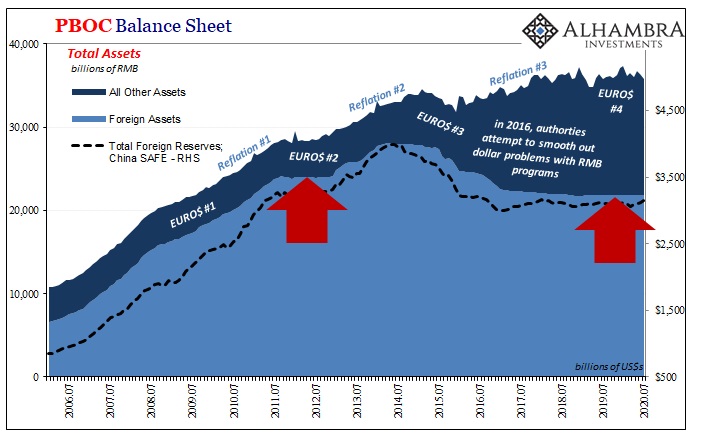

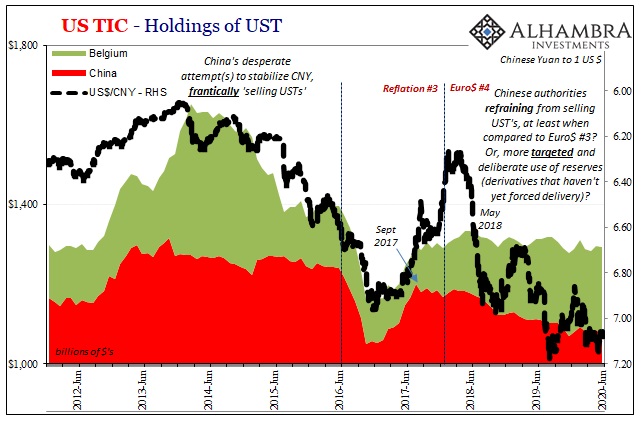

I’ve undertaken this review of the Brazil strategy because there seems to be a Chinese corollary to it. First off, the idea that China would adopt this type of policy already proposes just how desperate their situation must be; you don’t go down a dark and troubled road of proven failure if you have better options. CNY down around 7 already says as much.

If there is a difference between the Brazilian mechanics and their Chinese counterparts, it seems that “contingent liabilities” in the Chinese sense are much easier to hide. Brazil, unlike China, subscribes to global conventions including honestly filling out the pertinent IMF documentation (Section IV, to be specific).

China, on the other hand, is, well:

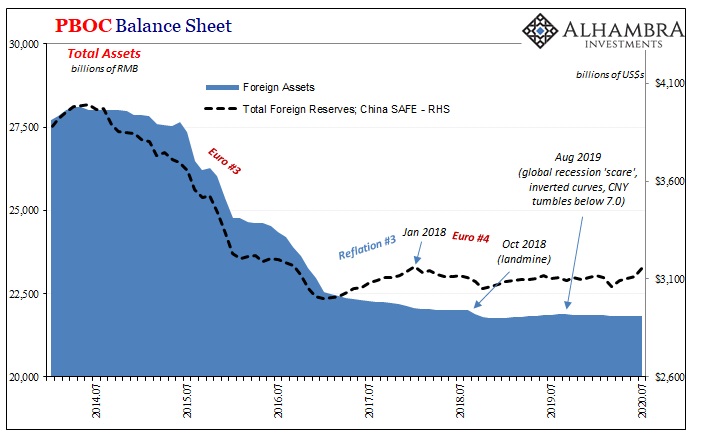

The exact mechanics of these swaps aren’t known. We can sketch out their rough outlines, always keeping in mind we are working in the dark (shadow money, after all). State-owned Chinese banks were borrowing “dollars” via increasingly expensive swaps with eurodollar banks and then selling them domestically in cash to dollar-starved local banks desperate for them (shorts and shortages).

They did so because like in Brazil the central bank was subsidizing the swap via its own forwards, liquidity backstops, and I think even some term repos collateralized by those UST’s it holds. But where does the central bank end of these triparty transactions show up?

Ironically, it shows up on the central bank’s balance sheet, I believe, in the absence of it showing up. What I mean by that is the obvious engineering in China’s foreign reserves; even more of a straight line where these are held at the central bank. Such evenness in such a dynamic and drastically complex account can only be the product of intent.

Like Brazil, the reasoning behind it we can easily understand. Unlike Brazil, will it pay off?

Well, it actually had for the South Americans…for a time. Ultimately, however, they were undone by largesse. You simply cannot hide nor obscure a huge problem forever, and if you have that big of a dollar problem to begin with, is it at all likely to be nothing more than a temporary setback?

Someone is bound to notice.

We already know China’s big dollar problem has been a fixture of its economic and monetary system since 2013 (not coincidence the same timing as Brazil). After all, 2018’s petroyuan introduction was about doing something tangible to reduce that pressure (rather than replace the dollar which RMB simply cannot do).

With CNY now up into the 6.80’s from a low near 7.20 (to the dollar), it would otherwise seem like strength consistent with dollar “inflows” and reflation across the globe. Except, as noted by others here, something seems to be missing from them and it’s becoming noticeable. About $100 billion according to their calculations (I’d wager it’s much more than that).

Two of the four possible explanations for the discrepancy offered by the analyst were rejected because they were inconsistent with the concept of “inflows.” The pair, the bottom two, shown below, are immediately recognizable to shadow eurodollar observers:

What could be the possible explanations? Wrigley proposed a few possible theories:

1. Chinese companies paying down foreign debt or hoarding dollars.

2. State banks building up foreign currency assets.

3. Foreign companies in China reducing yuan assets or taking money out of China.

4. Capital flight.

Though I wouldn’t dismiss #1 so easily, given where we are right now, and where we are right now is the opposite of a world flooded with dollars, many eurodollar observers will note #’s 3 and 4 have been consistently confused with eurodollar problems ever since 2013.

Throughout 2014 and 2015, for example, while China was furiously selling down its dollar reserves the mainstream media kept characterizing the Chinese problem as “capital flight”; something about rich billionaires trying to get out of Beijing. No sir. Dollar destruction, pure and simple.

In the context of the PBOC’s 2019-20 straight line for its forex asset base, why would anyone rule out “contingent liabilities” masking an otherwise relatively straightforward eurodollar squeeze? We understand both why the Chinese would want to hide such a thing, as well as the general idea about how that would work. Not the specifics; we’ll never be privy to those, but we’d expect a contingent inflow only in the one sense that in others looks like the same old outflow.

Then again, why would anyone question Jay Powell’s abilities as a monetary wizard, meaning how there could only be inflows of dollars to each and every corner of the world because of the massive, and inflationary, monetary flood he constantly talks about. It was reported as fact all over the media, in all the papers, TV, and across the entire internet.

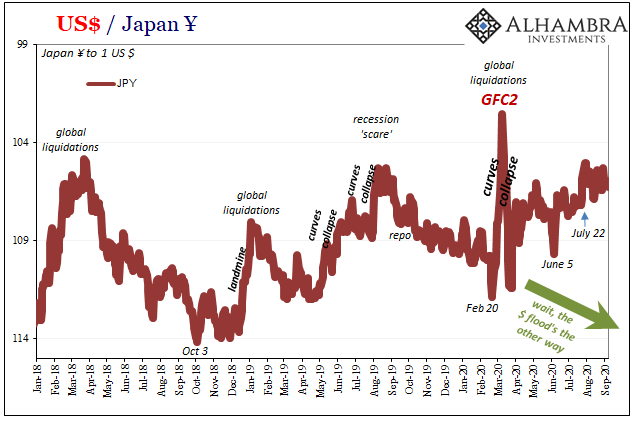

I mean, so massive it’s not like China’s major redistribution source for dollars, Japan, suggests anything like further outflows…oh crap.

Stay In Touch