Everyone was really confused. China was the unstoppable monster, the economic powerhouse that had quite easily, it seemed, survived the Great “Recession” with barely a scratch. Its ascent to the dominant world position had been written long ago in stone, carved macro graffiti left in place especially as the so-called developed world struggled mightily after 2009.

The Chinese were widely thought invulnerable to whatever it might have been (sure, they said subprime mortgages) suffering its Western competitors. As a consequence, China’s currency (yuan, or just CNY for short) was universally expected to continue its upward climb reflecting its ascendant status.

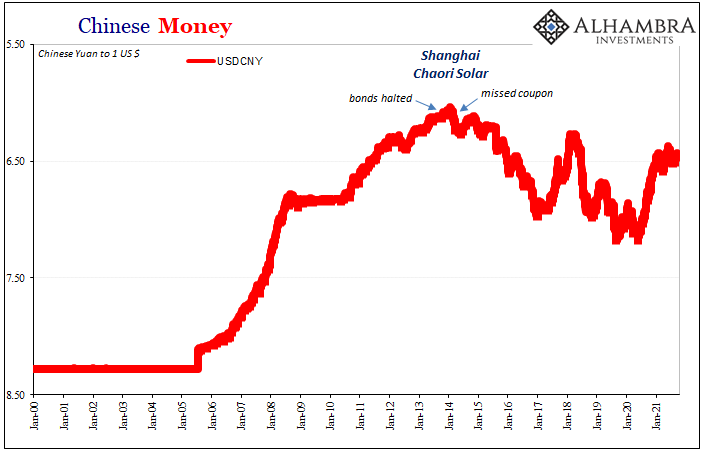

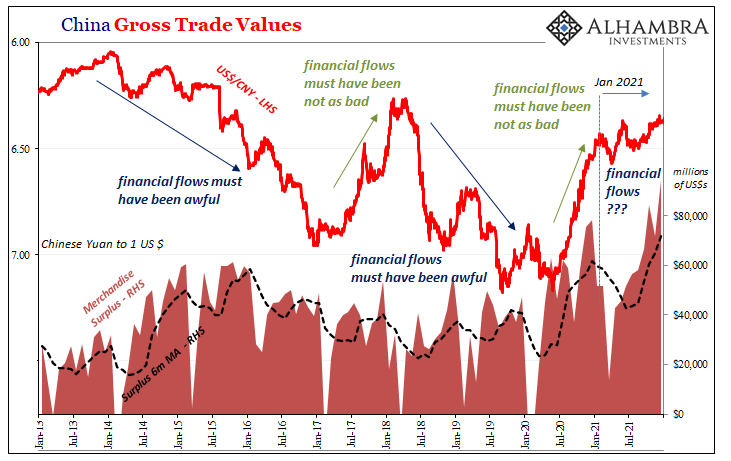

Right at the outset of 2014, however, CNY abruptly changed direction. And this was no little market fluctuation, either, a full-on dry heave which left the world stunned – including Chinese policymakers who by March of that year rushed to reassure onlookers they were very much in control.

Spoiler: they were not in control.

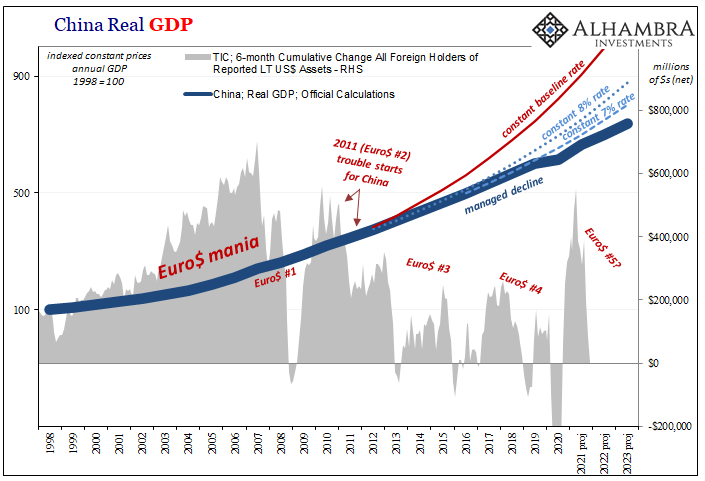

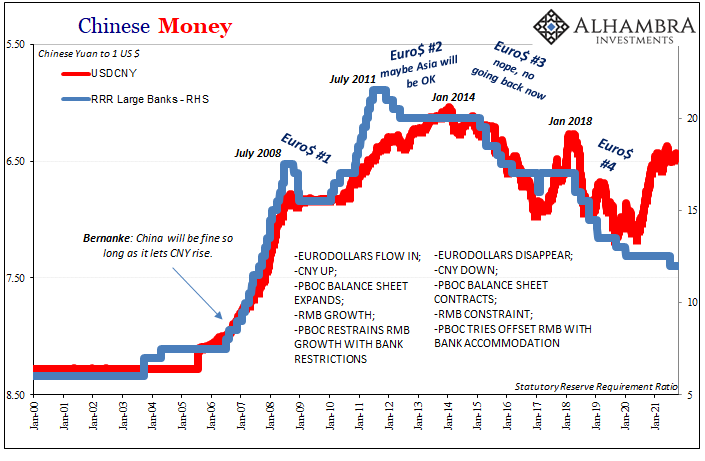

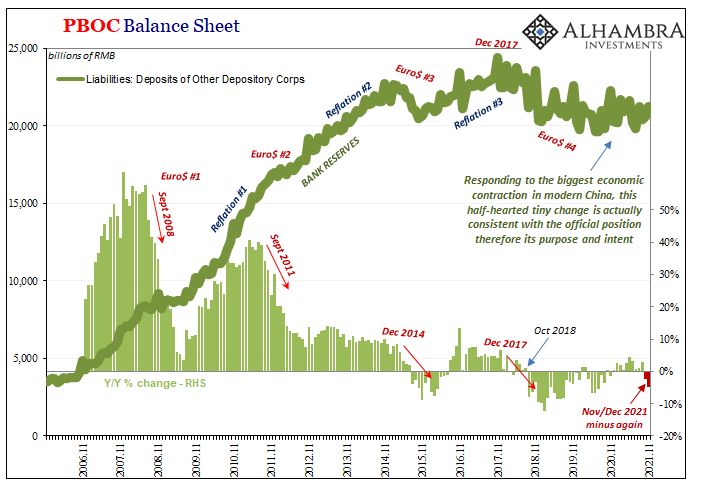

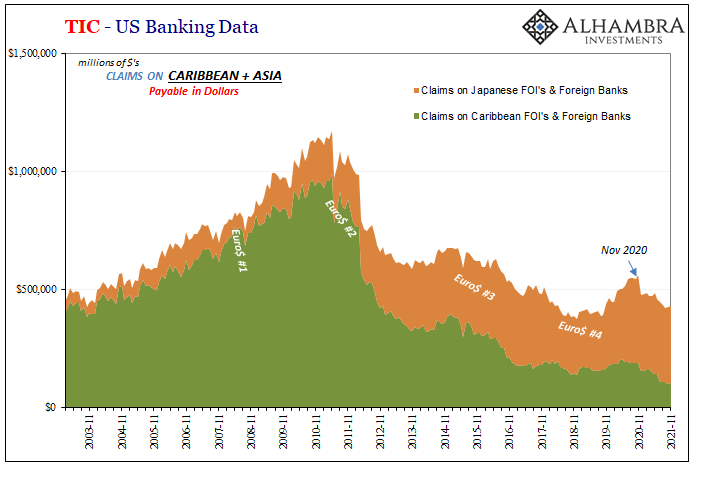

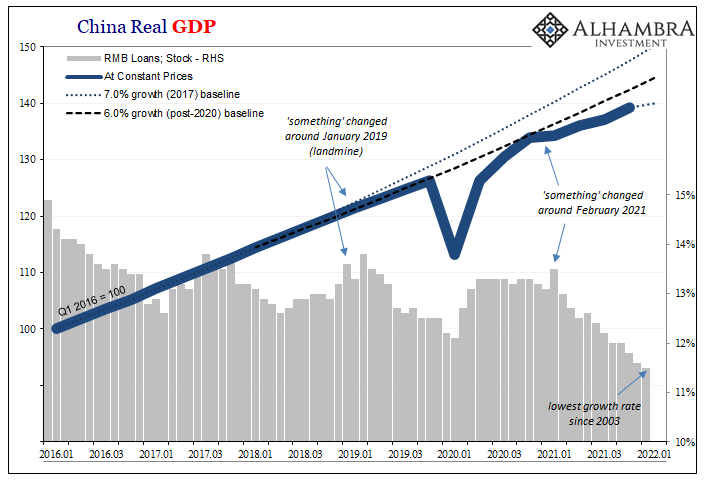

Two things first: China’s economy actually topped out in 2011 and began to slowly slow (second derivative) after Euro$ #2. It may have been imperceptible at this early stage, at least if you weren’t paying close enough attention, but the warnings gathered over those few years in between the climax and CNY’s directional change.

Quite a lot “interesting” happened especially summertime 2013. As growth faded, risks went way up including by external perception. Ignored in the mainstream as CNY looked unbothered, in actual global money this was huge. Never more so than when in the heat of mid-2013 an actual corporate default became likely.

Chaori would become a quasi-household name that year once trading in its bonds were halted signaling how a default event for them was pretty much inevitable. While distracted via the wrong interpretation of “taper tantrum” on this side of the Pacific, the markets in China were embroiled in a confusing ocean of sudden chaos during the hottest months of 2013 (the Summer of SHIBOR).

An economy decelerating when it was supposed to easily recover to pre-crisis status and then, shock, prospect of unpaid bonds for a first time. Under Deng Xiaoping’s market-friendlier version of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics the government had prioritized economic growth over all (grow wealthy or suffer the fate Mao had left for Deng, the very result witnessed in Russia right next door). Failure – of the financial kind – was never an option.

Until it was.

As Chaori’s drama unfolded, the eurodollars first slowed (SHIBOR Summer) then disappeared. This was the first few months of 2014 and then March; CNY reversed course and headed downward no matter any PBOC jawboning or eventually several “rescues.” My perceptions of that mid-March were very different:

What all this data shows, as opposed to conjecture about the supernatural powers of central banks, is that yuan’s devaluation may be directly tied to dollar shortages. In fact, as I argue here, it is far more plausible that a dollar shortage (showing up as a rising dollar, or depreciating yuan) is forcing the PBOC to allow a wider band in order that Chinese banks can more “aggressively” obtain dollars they desperately need. Worse than that, the PBOC itself cannot meet that need with its own “reserve” actions without further upsetting the entire fragile system.

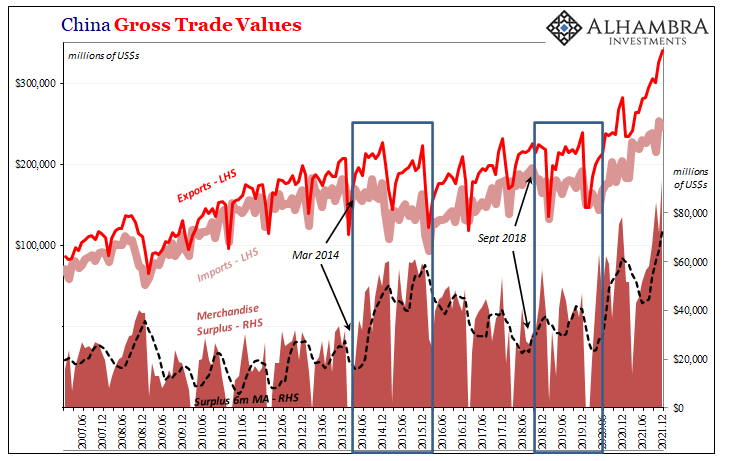

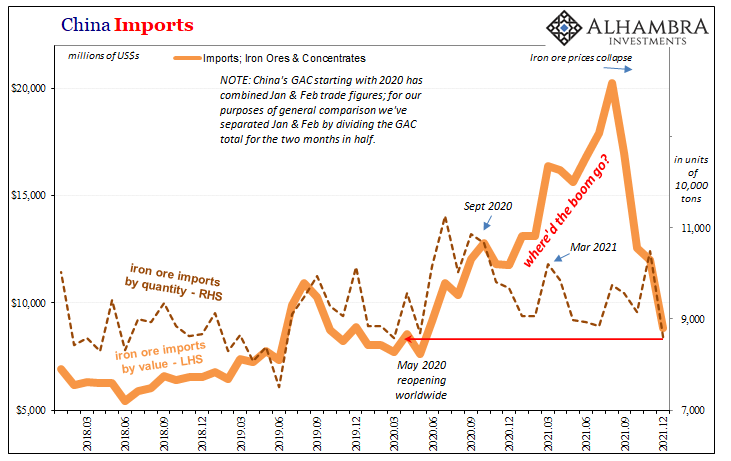

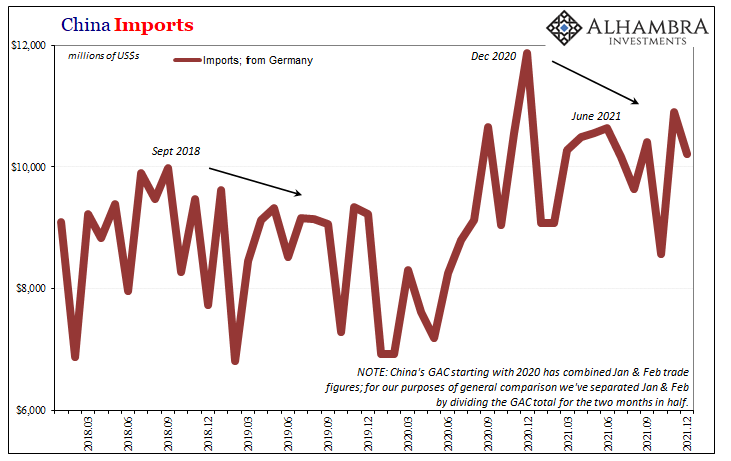

The purpose of this Euro$ #3 review is to link the money with the economy more directly and not just for China. CNY fell as an indication of dollar shortage. That caused harm internally to China, yes, but also transmitted externally via Chinese imports. The whole matter descending further toward the chaotic, China perhaps naturally and reflexively began to cut way back on their imports (see: below). Yes, a weakening internal economy being further sapped by China’s eurodollar external to internal money connection (see: above; RMB being dollarized therefore fewer dollars leading to fewer RMB particularly bank reserves, also currency), but also dollar preservation.

The whole matter descending further toward the chaotic, China perhaps naturally and reflexively began to cut way back on their imports (see: below). Yes, a weakening internal economy being further sapped by China’s eurodollar external to internal money connection (see: above; RMB being dollarized therefore fewer dollars leading to fewer RMB particularly bank reserves, also currency), but also dollar preservation.

They have to pay for imported goods largely in US$s the same as everyone else via these same eurodollar channels. If the country and its top-down management authority realistically figures fewer dollars will be available – or, as in this extreme case, they begin to disappear by the hundreds of billions – then it makes perfect sense to scale back the purchase of imports as a means to conserve whatever dollars.

Unsurprisingly, imports contracted massively far and above the decline in exports from China (as noted a few days ago, a merchandise-based source of some dollars) beginning around March 2014.

Their eurodollar problem only worsened afterward and then became a primary reason (alongside internal weakness) to sharply curtail acquisitions of material on global markets, thereby transmitting the money issue to the rest of the world in the form of sharply lower global trade overall highly dependent on China.

The rest of the global economy, other emerging markets nations in particular, suffered mightily for this (as well as their own dollar problems).

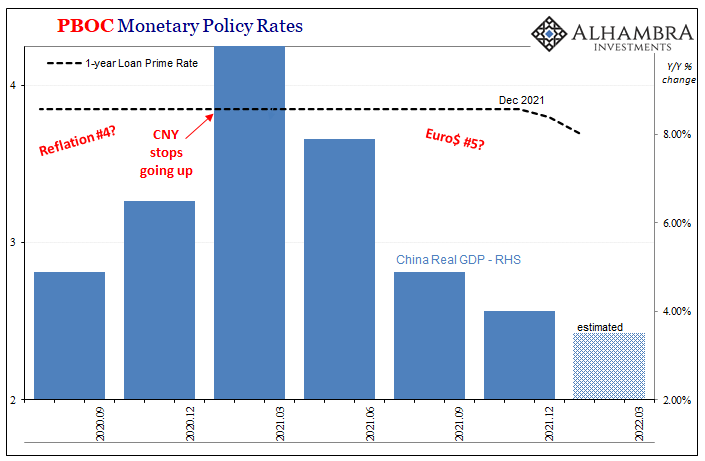

This transmission would get repeated during Euro$ #4 when China after September 2018 with its currency already plummeting (remember Urjit Patel just a few months prior: “…dollar funding has evaporated”) and then October 2018 the global landmine develops and thereafter Chinese imports again decline more than imports.

As before, weakening internal situation, yes, but also dollar preservation as shown above as a rising merchandise surplus posted during that pre-COVID global downturn.

If China does experience a eurodollar repeat in 2022, if it hadn’t already to some extent in 2021, what risks in terms of global trade? They should be the same in all likelihood.

As 2018, without any visible, tangible proof of much or any inflows during the “good” times of 2017 or 2020-21, Chinese authorities must know they are exposed to eurodollar outflows and by how much (or have some fuzzy idea in the ballpark). Should these intensify or even just persist, at what point does the government repeat dollar-preservation and start materially cutting back on imports again?

Have they already in some places perhaps obscured somewhat by the price illusion? Imagine of Chinese exports, and a key source of dollars, cools off at the same time.

Add those risks the same one for the internal Chinese economy yet again struggling, the flattening Treasury yield curve in the US makes a ton of sense for what’s going on outside of the country as well as the “inflation” and labor problems inside.

Stay In Touch