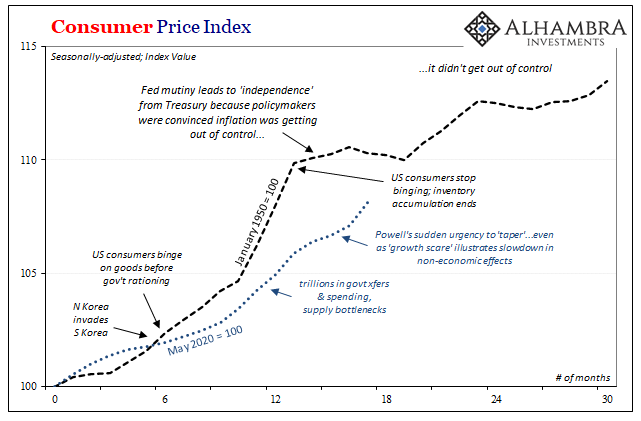

The BLS said today its Consumer Price Index rose by 6.2% in October 2021 when compared to October 2020. This was the largest annual increase since Alan Greenspan was giving up on M2 three decades ago. Perhaps most concerning, after having taken a few months “off” prices re-accelerated last month reigniting fears of a 70s-style monetary runaway.

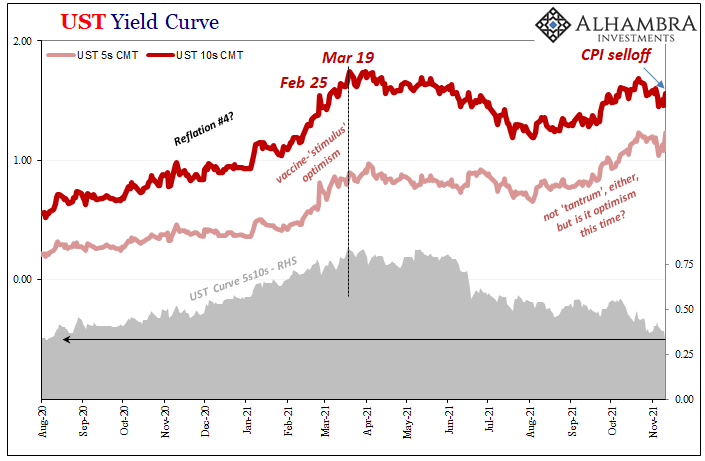

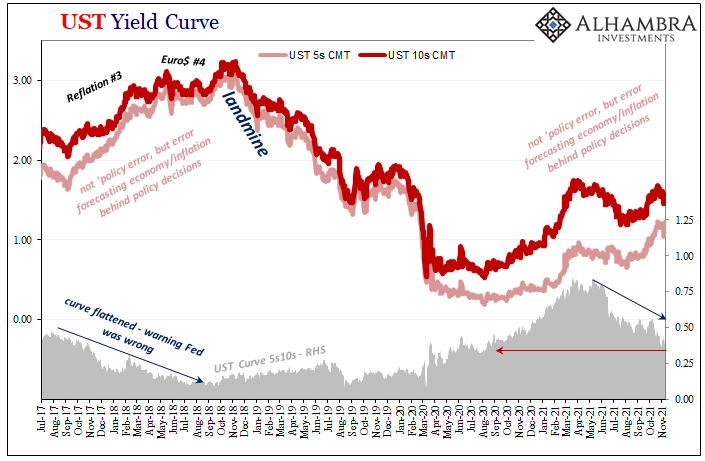

But, as we saw earlier in the year when CPI’s were “surprisingly” rollicking, the bond market’s reaction was swift yet largely the same. Even today when longer-end yields rose precipitously, a real selloff, the yield curve itself continued to flatten as it has for two-thirds of a year. The fundamentally important 5-year to 10-year calendar spread (5s10s) dove down to 34 bps – the flattest this key piece of the curve has been since early August 2020, practically the moment this “reflation” trend kicked off.

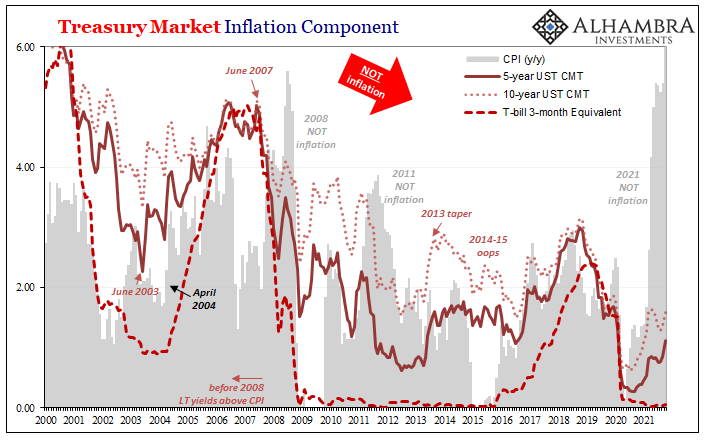

Not only are yields still signaling “transitory”, they remain firmly convinced that this “inflation” isn’t.

The flattening curve indicates a couple of important judgments (from the inside of the monetary system). The first is the FOMC very likely to continue if not accelerate its taper in search of its first rate hike. Think 2014-16 (not in a good way).

Longer-term yields strongly suggest the reasons for this “hawkish” development continue to be – as they have been since mid-March eight months ago! – all wrong. In one sense, it may be that the market is taking account of the CPI as representing just one more negative to pile on to a growing pile of negatives.

In other words, the (global) economy is already slowing down and, non-inflation or not, these painful consumer price increases, particularly gasoline, will make this slowdown all the more difficult (and uncertain) to navigate.

Because consumer prices are being pushed by non-economic, non-money reasons, one way to hasten the inevitable downside adjustment in them is when consumers (and producers who are getting squeezed at their margins) are robbed of discretionary power right when the economy can ill-afford anything less than perfect. It is both the 2008 as well as 2011 scenario (and 2018, to an extent).

This is the only way to reconcile yields otherwise fervently ignoring these “inflation” results; and ignore absolutely includes the fact how even after today’s market selloff, 10-year like 30-year yields are still less than they were all those eight months and five 5-plus-percent CPI’s in between.

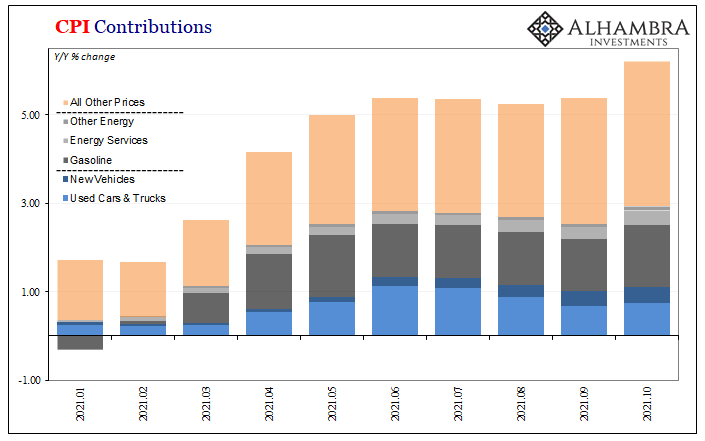

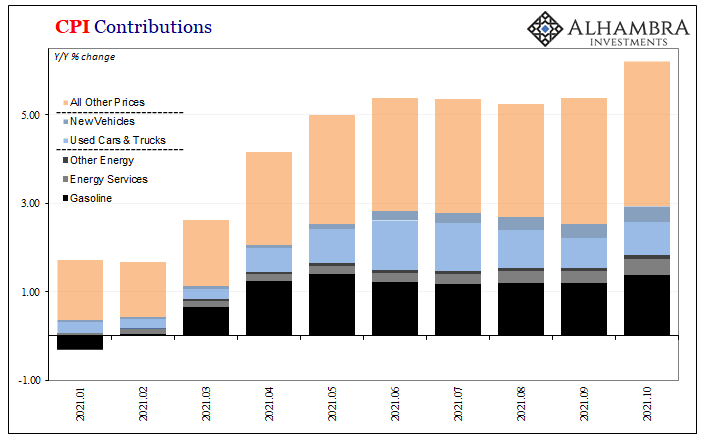

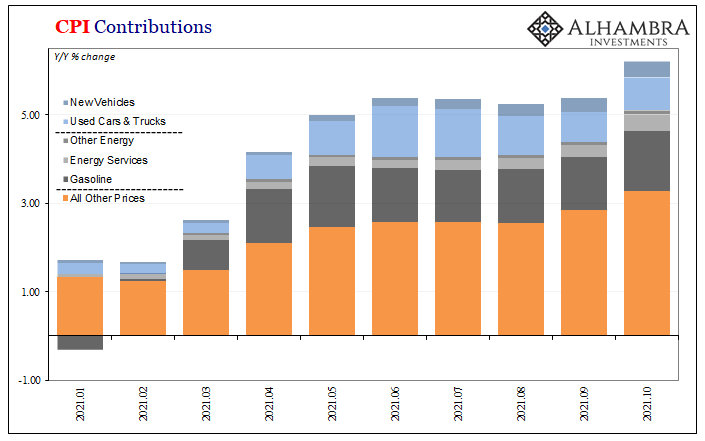

Digging into them, again in October there remains every reason to believe transitory on the basis of clearly supply rather than money (or even macro) factors. Start with those components of the CPI bucket which come from the most obvious supply-stretched sectors: energy and cars.

Of the 6.2% year-over-year increase in October, just about half (47.3%) of that rate was due to those two. And it’s been this way ever since consumer prices got going in March.

At first, energy contributed the most in the initial burst, then cars (mostly used car prices) took up in the middle, and now more energy (especially gasoline, but also an unhealthy rise in energy services, meaning utility costs).

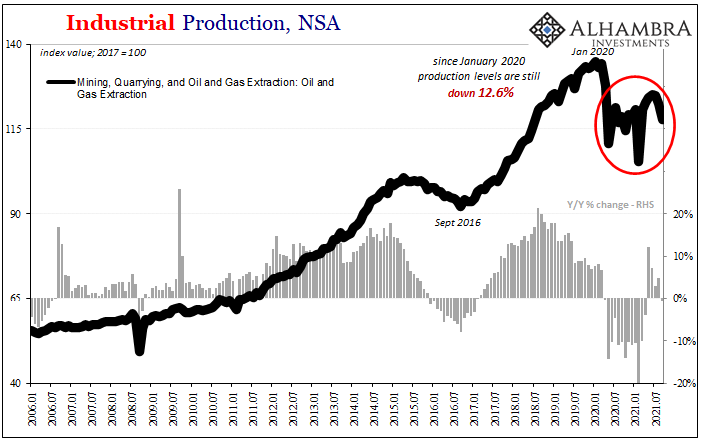

We know what’s behind oil prices, and it isn’t QE. Not only is OPEC refusing to step up production globally, American producers also seem to be waiting for…something. According to separate Federal Reserve data (IP), domestic oil and natural gas production in September (latest figures) had been a ridiculous 12.6% below peak output way back in January 2020.

Is that COVID? Capital goods bottlenecks? Perhaps skittish oil drillers who aren’t really sure about turning on expensive, potentially unprofitable wells when they may not believe oil prices in the $80s are going to stay in the $80s (or $70s, for that matter) once all the artificial stuff from earlier in the year further fades out.

As to automobiles and vehicle prices, one need only look at dealer lots to find the issue with those prices.

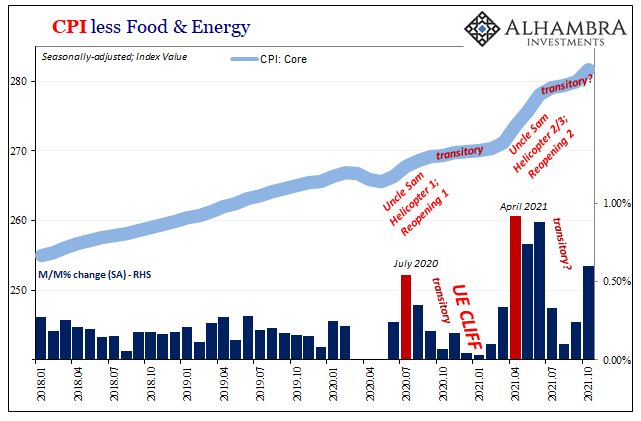

This isn’t to claim that outside of these segments there is no consumer price deviation; to the contrary, even core rates had accelerated in October, as they had earlier in the year. The pattern, however, is the same as those above indicating the same thing as those other parts of the consumer price bucket where cause-effect is so clear.

What’s therefore happening is the most obvious supply imbalances are leading to the most obvious upward price effects thereby greatly amplifying those other narrow factors into a steady stream of 2008-style (yep, ’08) CPI numbers.

And given the nature of the American calendar along with these problems up and down the whole consumer landscape, not even transitory was going to go in a straight line. Kinks and quirks will abound, as they have throughout history. As noted yesterday:

“Customers are just flinging crazy orders right now, so it’s hard to determine the real level of demand,” said the chief executive of Kids2, the Atlanta-based toy company best known as the maker of Baby Einstein and other baby-oriented brands. Business always surges around the holidays, but this year has been turned on its head by the pandemic.

Along with those more evident imbalances between supply and demand in oil and cars, the Christmas rush in October could very well account for the CPI results, too. After all, the public has been warned their Christmas would be in jeopardy if they didn’t get a jump on everything; even Amazon’s you-can-have-it-tomorrow lineup has been careful to nudge more toward preorder.

What the bond market cannot do is tell you much about how A becomes B, where A was 2021-style “inflation” and B is the unavoidable other side of it. The yield curve instead is a wealth of information describing what B looks like as well as the probability (inevitability) it ends up that way.

How can the entire market, today’s action notwithstanding (see: April BLS release), price a 6% CPI with a flattening curve like this? If it’s still not inflation and what “inflation” that CPI represents actually contributes to the downside by harming consumers (and businesses) already getting stuck with a global economy more and more likely rolling over.

And I haven’t even written about money and what “bonds” say about that. Without the actual monetary binge, even a consumer binge just won’t bring inflation no matter how high the annual consumer price rates in between.

Stay In Touch