It was the clash of all clashes, the textbook up against practice in a real world falling apart. Theory’s chance to save the day and prove itself, what should’ve been the legend’s finest hour. Time to put up, or…

On the one side, there was the “money” we’re all told is easily created, and on the other what may have seemed a weird quirk of deep inside baseball applicable only to mathematical junkies and bond traders (often the same thing). Unfortunately for the world, and everyone in it, the “money” lost in a rout to the oddity (several of them, actually, all related).

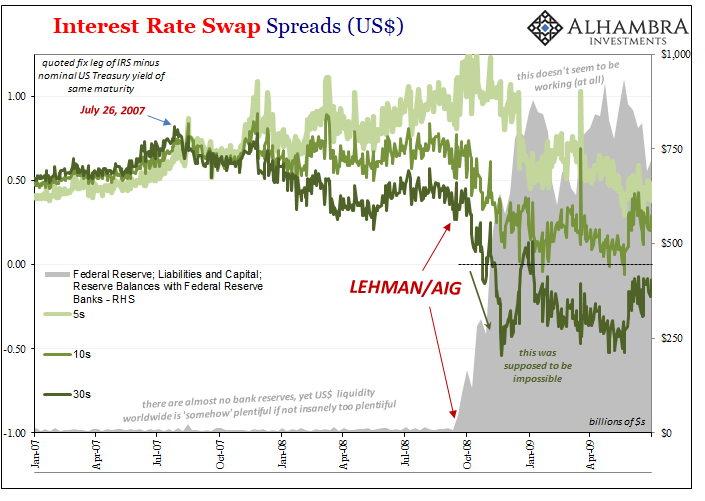

It’s worth one more time revisiting the numbers first. The week before Lehman Brothers, there had only been about $9 billion in total bank reserves throughout the entire world. Seriously, that’s all there were for a tens of trillions-sized globe-spanning monetary system. Before the events of the first GFC, the global monetary system didn’t need them because it had created and maintained its own zoo of liquidity with its own forms of exotic moneys.

Despite all the crisis rescues offered between when it first erupted in August 2007 and when it went globally nuclear in September 2008, the Federal Reserve had always been careful to sterilize whatever was done so as to not unleash the full inflation of what the textbook had said would be this incredibly potent tide of bank reserves liquidity.

The extraordinarily harsh circumstances pounding the zoo, however, convinced Ben Bernanke and his fellow policymakers that they should abandon all caution and “print” “money” without any regard for past fears and restraint. In just eight weeks up to the middle of November (when TARP “had” to be changed), $620 billion of those bank reserves had been conjured out of thin air.

And then $240 billion more were added on top to close out the year.

To put these numbers into some perspective, in the aftermath of September 11 seven Septembers before all this, Alan Greenspan’s Fed had allowed $67 billion in bank reserves, a princely sum at the time nearly double what had previously been the highest level simply because so much of the Wall Street’s physical infrastructure had been destroyed.

What was being printed up by the end of 2008 would total thirteen times that.

In other words, the amount of bank reserves had been increased 97-fold from just before Lehman, ending up (for the time being until the QE’s) with about 22 times more bank reserves than at any other time apart from September 2001.

A flood of “money”, some might’ve called it.

And yet, at the very same time as this “flood” from mid-September onward, the US as well as the rest of the world experienced its worst monetary disaster since the early 1930s.

These facts of late 2008 (and early 2009) are perfectly clear. Chaos. Panic. Worldwide contagion. An overflowing surplus of bank reserves. One of these things is not like the others.

How could we possibly have had skyrocketing mounds of money, abundant to overflowing bank reserves at the very same time as unrelenting global monetary crisis?

Bank reserves cannot be a useful form of money.

This inescapable conclusion leaves us with a whole range of huge questions whose answers hold the most profound implications. If bank reserves are not money, what does the Federal Reserve actually do? What even is the Fed? And if what the Fed does isn’t money, then what is?

As to the last of those, we can turn to something like swap spreads to begin piecing together its solution. Right in the thick of that 97-fold flood of bank reserves, the spreads on interest rate swaps (fixed leg) compared to the same maturity nominal US Treasury yields absolutely collapsed – including a negative 30-year swap spread that had been previously thought impossible.

October 23, 2008, was an unusual day in credit markets even within a vast sea of unusual days. Credit and “exotics” desks at banks were left scrambling to figure out how it was possible that the 30-year swap rate could trade less than the 30-year treasury. It was thought one of those immutable laws of finance that no such might occur, to the point there were stories (apocryphal or not, the tale is about the scale of disbelief) that some trading machines were never programmed to accept a negative swap spread input.

By October 23, bank reserves were a full third of the way up, totaling $301 billion just as swap spreads had gone way, way down. Sadly, only the latter ended up meaning anything.

The financial system had broken down because money elasticity was far outside the boundaries of the Federal Reserve’s outdated, anachronistic framework. A negative swap spread appears to mean the market views the US federal government as more of a credit risk than the bank counterparty on the other side of the interest rate swap; the same bank back then at risk of being run over by the ongoing global bank run.

No. The negative swap spread was, and sadly remains, gibberish; though a particularly informative sort of gibberish.

Take a swap spread, for example. A negative one means what? In textbook terms, if the fixed rate paid on an IRS is less than the risk-free UST yield, this would appear to indicate the market is judging the US government as the riskier counterparty. Nonsense. Quite literally nonsense.

What’s left out of the Economics textbook and never makes its appearance on CNBC or in the FOMC’s boardroom is how it requires banks and specifically money dealer banks to make sense of money in operation. Markets are messy, so to achieve order out of chaos it absolutely requires policing. Arbitrage and the capacity to undertake it.

Forget what a negative swap spread or upside down repo “means”, simply ask yourself, where are the dealers? In other words, whenever we see this nonsense it tells us that something, some great monetary capacity is surely missing.

Thus, whereas bank reserves throughout the complete Autumn of 2008 were in historical excess the level of monetary sufficiency in the form of balance sheet capacity was…not.

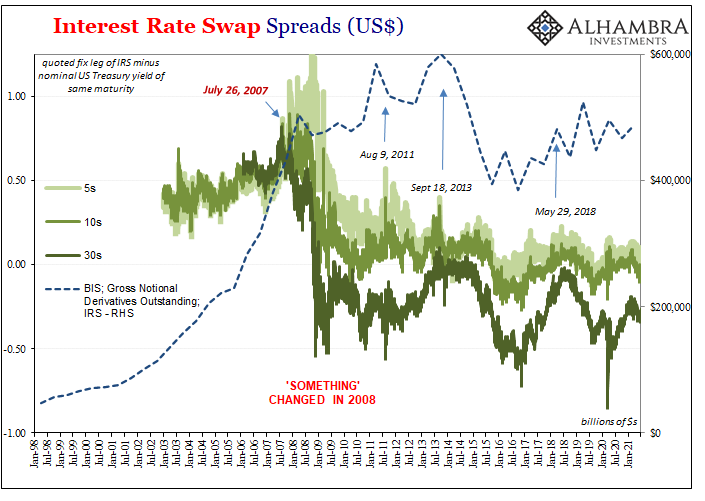

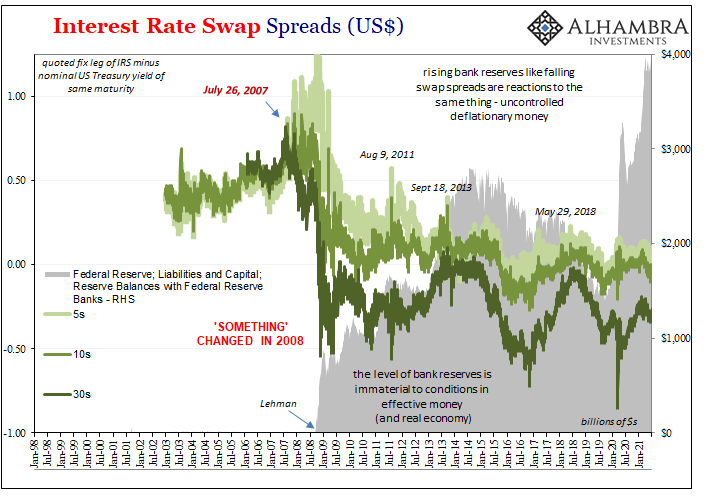

No Dodd-Frank nor Basel 3 was ever needed to suppress the dealer instincts of the true guts of the global monetary system. Those came along much later, long after the full – and permanent – damage had been suffered. The permanent rupture is clearly marked in 2008; all Bernanke’s reserves of horses, and all Powell’s QE’s of men, neither have ever put the system back together again at any level of bank reserves.

Swap spreads give us a very clean sense of monetary mechanics in their truest sense of effective eurodollar use. That’s the good news.

The bad news, as delivered late last week, is what that sense of swap spreads has been throughout.

In the long run big picture, well, see: above.

Again, balance sheet capacity indicated by all these spreads regardless of regulations (including the shot-in-the-dark idea that clearinghouse usage maybe, possibly could kind of explain part of this permanent spread compression) remains unambiguous. The only upside visible at any point over the more than decade since is the same unsatisfactory upside in the global real economy; partial reflation(s), at best.

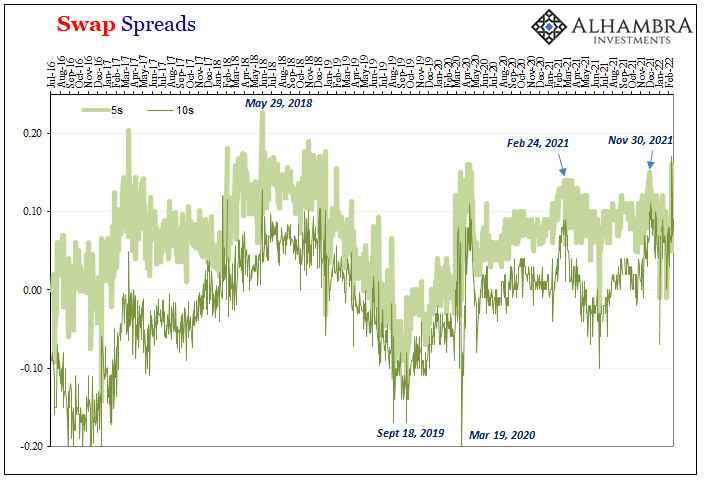

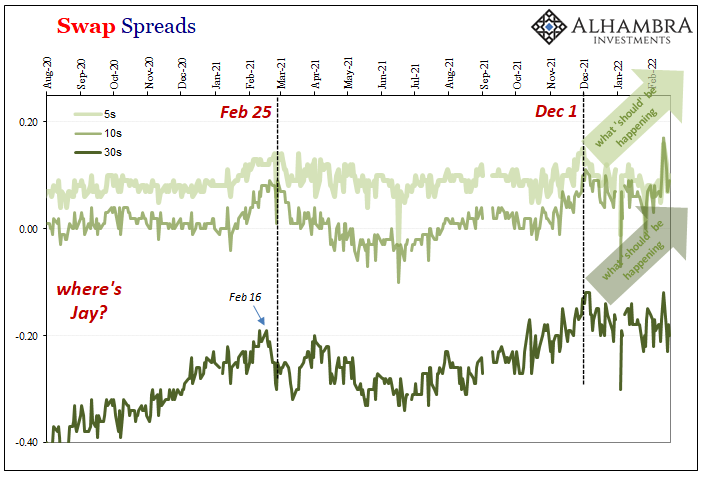

This includes, starting with the swaps market, 2021 and 2022. In fact, last year hadn’t even replicated the reflation in spreads of prior years even as the idea of uncontrolled inflation took hold largely on the basis of assumed monetary excesses.

As noted to end last week, since specifically December 1, 2021, spreads are compressed everywhere despite what should be the most intense pressure on them to decompress – either that presumed inflationary currency therefore expanding nominal balance sheets (what would have to be the real money of inflation), or rate hikes the Federal Reserve is almost certain to get going within a matter of weeks.

Regardless of either, coinciding (not by random coincidence) with eurodollar futures inversion, swap spreads aren’t behaving. Instead, they’re doing their thing again this time with several trillion more in bank reserves.

Swap spreads. Eurodollar futures. Flat curves galore. Those are the actual flood…of nothing has changed. All the money indications we have, consistent, historically validated, they aren’t figuring inflation; or even much of rate hikes. Like so many times since before Lehman, ask yourself why.

Stay In Touch